- What Studies in Spatial Development Show in Ethiopia-Part I

- What Studies in Spatial Development Show in Ethiopia-Part II

By Michael Geiger, co-authored by Priyanka Kanth (The World Bank Group) |

The Country Partnership Framework (CPF) for the coming five years in Ethiopia, approved by the World Bank board in June, features a “spatial lens” for development activities. This lens was developed in a background note we wrote evaluating spatial disparities and their related challenges. In it, we looked at the policy framework put forward by the 2009 World Development Report “Reshaping Economic Geography,” and combined it with literature on pro-poor growth. Together, these have allowed us to put forward policy solutions Ethiopia could adopt to bridge spatial disparities.

In this three-part blog series, we present the key findings of our note, as well as broad, overarching policy solutions.

The guiding questions in our evaluation were: How to integrate the poorest, rural, bottom 40 percent (“Bottom 40” or “B40”) of the population in the overall growth process? How can areas of high B40 concentration be better linked to centers of economic activity?

We also looked at how to create larger urban centers, ones to which rural areas can be linked? And how to increase the capacity of these urban centers to address urban poverty?

Rapid economic growth

Ethiopia is a fast-growing economy, with double-digit growth in the past decade, and prior growth that also drastically reduced poverty from 2000 to 2011—from 55.3 to 33.5 per cent of the population (based on the poverty rate of US$1.90/day). Despite its large population of about 100 million, the country also has one of the world’s lowest rates of inequality, with a Gini coefficient of 0.3.

That said, rapid growth has not reduced inequality for the very poorest.

For instance, the Systematic Country Diagnostic (SCD) showed that the poorest 10 percent of the population experienced a decline in consumption, implying that reductions in overall poverty rates were not matched by reductions in its depth and severity among all those experiencing it.

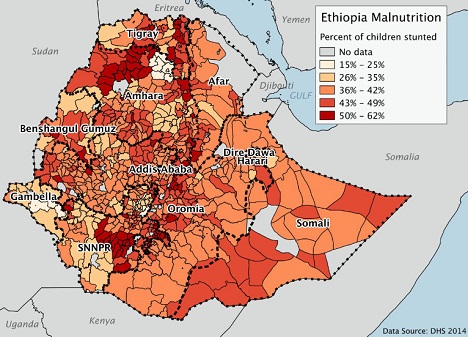

For analysis on this, we conducted geo-mapping exercises, and verified findings against data available for Ethiopia.

Read the complete story (Part I) here

And, What Studies in Spatial Development Show in Ethiopia-Part II here

——

See also:

- Agro-industry: Crucial for Ethiopia’s Economic Development

- UNDP Launches Study on Income Inequality in Sub-Saharan Africa

- EVENT: The First Annual Conference on Human Capital Development in Africa

- Africa’s Economic Giants Face Increasing Competition from Upcoming Kenya and Ethiopia

- World Bank’s Global Outlook Considers Ethiopia as the World’s Second Fastest-growing Economy