When Mohamad Nasir first met Bill Gates in 2012 in his home country of Ethiopia, the child was less than a month old and had recently received vaccinations against polio, measles, and more.

By Alexandra Sifferlin (TIME)

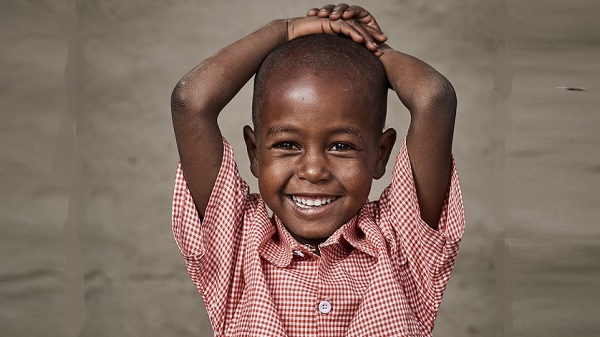

When Mohamad Nasir first met Bill Gates in 2012 in his home country of Ethiopia, the child was less than a month old and had recently received vaccinations against polio, measles, and more. Today, thanks to his early and ongoing health care, Mohamad Nasir is an active and curious five-year-old who loves sports and is quick to welcome a visitor. Mohamad Nasir’s life represents an important milestone for his community and for the world.

In 1990, the number of children who died in Ethiopia from preventable causes was staggering: one in five children didn’t live to their fifth birthday. In response, the country took substantial measures to combat the problem. In 2000, Ethiopia’s government made a commitment to improve health care and address the lack of health care providers in rural areas of the country.

Ethiopia was able to drop its mortality rates for children under-five death by two-thirds from 1990 and 2012—an impressive feat for a low-income country. Part of that strategy came from expanding community health care and training health extension workers. These workers are paid by the government to provide health services to people living in and around their village health posts, as well as make house calls and provide educational outreach activities.

Today, there are over 38,000 health extension workers in the country, providing a variety of services including giving vaccines, distributing reproductive health information and promoting good hygiene.

They include Yetagesu Alemu who was working out of the Germana Gale Health Post in rural Dalocha where Mohamad lives, over 100 miles outside the country’s capital, Addis Ababa, at the time of Gates’s visit.

“There is a lot of change in health care,” says Yetagesu, who now distributes vaccinations to combat eight different types of diseases. “The deaths of mothers and kids have been reduced. They were a big part of the population who was not coming to the hospital due to economical problems. Now these people can get free health services from nearby hospitals.”

“There is also a big educational push to teach people about health care and how to prevent sickness,” she adds. “This has improved the health condition of the country.”

Read the complete story at TIME

——

See also:

- Community Based Newborn Care (CBNC) in Ethiopia

- Ethiopia’s Ministry of Health Preparing National Food, Nutrition Policy

- Integrated Family Health Program: USAID Support Saved Lives and Improved Family Health

- The University of the Western Cape (Bellville, South Africa) Honors Ethiopia’s Health Minister

- Ethiopia’s Community Health Workers Strengthen Skills and Improve Care Using Smartphones