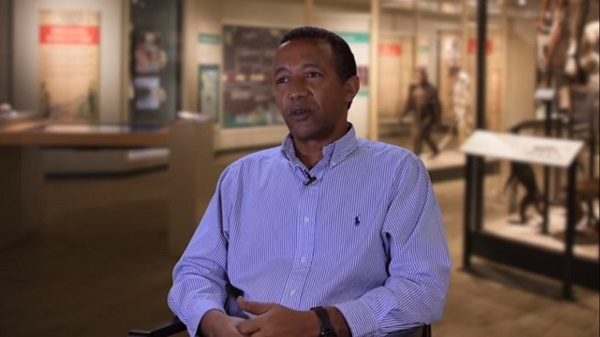

Native Ethiopian and a palaeontologist at the world-renowned Cleveland Museum of Natural History (Cleveland, OH), Yohannes Haile-Selassie, PhD, is named one of the ten people who mattered in science in 2019 by the prestigious journal Nature. Dr. Yohannes is also an adjunct associate professor at Mekelle University (Mekelle, Ethiopia) in the Institute of Paleoenvironment and Heritage Conservation.

Yohannes Haile-Selassie, PhD, Curator of Physical Anthropology, was recognized for his discovery of a 3.8-million-year-old fossil cranium of an early human ancestor in Ethiopia.

The partial skull of Australopithecus anamensis puts a face on a species closely related to the famous “Lucy” specimen’s Au. afarensis.

The discovery further challenged the long-held view that hominin evolution proceeded in a linear fashion, with one species disappearing and giving rise to its descendant species.

It was a pale, circular shape on the ground, about the width of a grapefruit, that caught the attention of Yohannes Haile-Selassie when he was investigating a site in the northern Ethiopian desert in February 2016. The object was jutting out of the parched earth just 3 meters away from a jawbone found by a goat herder a few hours earlier. “Before I picked it up, I said, ‘Oh my goodness, this is something.’”

The fossils together formed a remarkably complete early hominin skull, which Yohannes’s* team dated to 3.8 million years old. It belongs to a species called Australopithecus anamensis — the oldest and most elusive known human relative. That afternoon, the team celebrated their rare find with cold Cokes, beers and dancing.

The skull, known as ‘MRD’ and revealed to the world in August (Y. Haile-Selassie et al. Nature 573, 214–219; 2019), gave researchers their first look at the face of this enigmatic ancient relative, which was previously known from just a few bone fragments. Palaeoanthropologists are impressed by the specimen, and some say it is rivaled only by Lucy, the 3.2-million-year-old skeleton fossil of the closely related species Australopithecus afarensis. “That’s a big thing to hear from our colleagues,” says Dr. Yohannes.

Dr. Yohannes is considered one of the field’s most talented fossil finders. Many treasures have surfaced from his project in Woranso-Mille, a region scattered with hominin fossils from the Pliocene, a key period in the evolution of the genus Homo and its close relative Australopithecus between 5.3 million and 2.6 million years ago. He is also one of a crop of Ethiopian palaeoanthropologists who lead major scientific projects in their homeland — a big shift from a generation ago, when foreigners oversaw most of the research in this fossil-rich nation.

When Dr. Yohannes was doing his PhD in the mid-1990s, his potential was clear and he had a knack for both laboratory and fieldwork, says Tim White, a palaeoanthropologist at the University of California, Berkeley, and Dr. Yohannes’ PhD adviser. Fieldwork in remote areas is extremely difficult, says White, but Yohannes has nailed it: organizing people, equipment, vehicles and permits, and all using multiple languages. “It’s not luck that Yohannes put these people in Ethiopia in this place, with all the right specialists to work on a problem.”

Continue reading this story and see the complete list of Nature’s ten people who mattered in science in 2019 here.

* Ethiopians use patronymic names rather than family names. That is, a person in Ethiopia is addressed by his/her given name as there is no such thing as ‘family name’ or ‘inherited name.’